11/12/24 - Is the current crisis the fault of motorbikes?

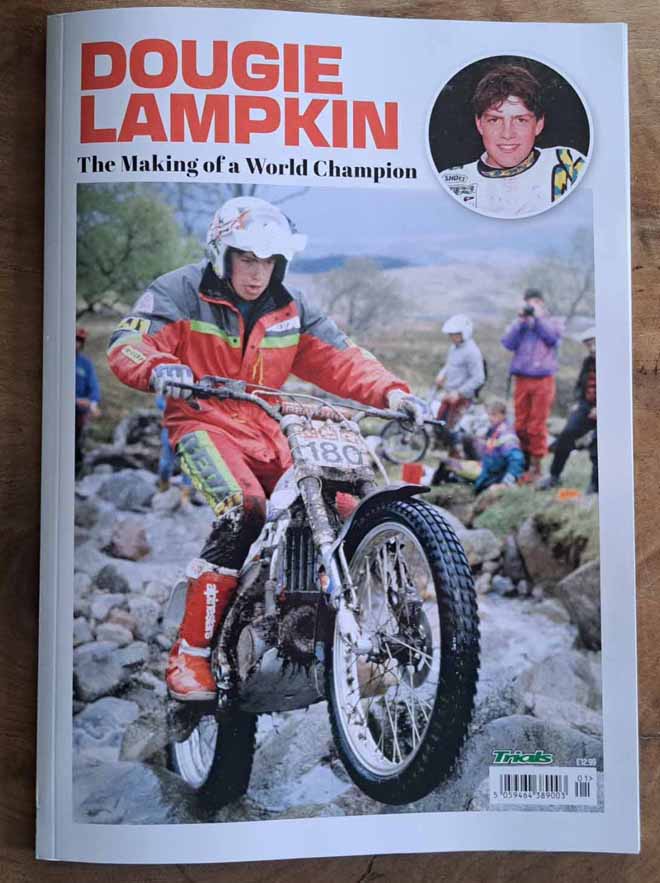

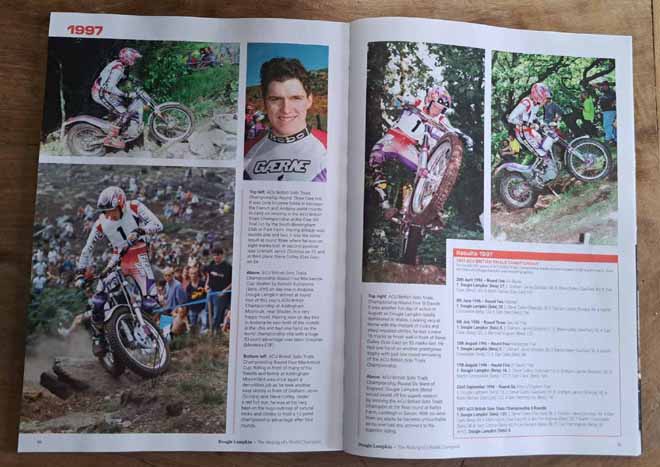

Reviewing the recent book produced by Trials Magazine UK on the growth of champion Dougie Lampkin, on the sacrifices, on the long periods of ups and downs before finally crowning the dream, the first outdoor world title, in 1997, the first of seven consecutive, it came naturally to open a window on that year, to compare ourselves and understand where we went wrong, if we made mistakes because probably nothing could have been done, to avoid reaching the profound crisis of today.

There was already talk of a crisis at the time because since the boom of the 80s the Trial has no longer grown in numbers, but all in all it was a bed of roses compared to what is happening today.

There were those who argued that motorbikes were becoming too sophisticated, suitable only for sporting use and therefore narrowing the user base, with those non-existent saddles, with those increasingly powerful engines and increasingly reactive suspensions.

But progress could not and cannot be stopped. The International Federation was starting to act on the Regulations, which had not been touched for too many years, thinking of creating new motivations.

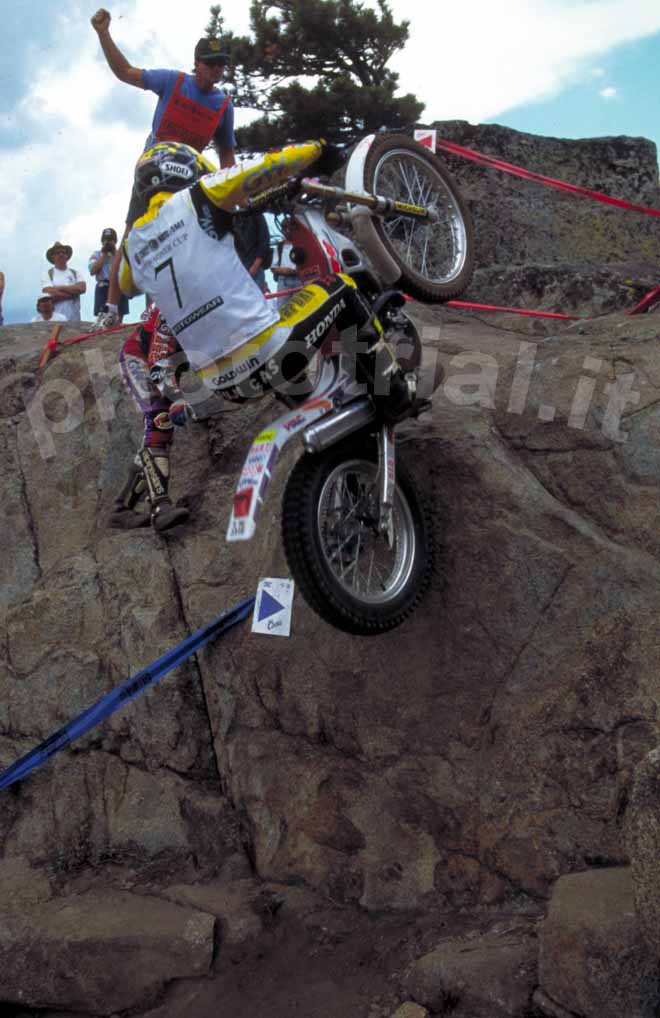

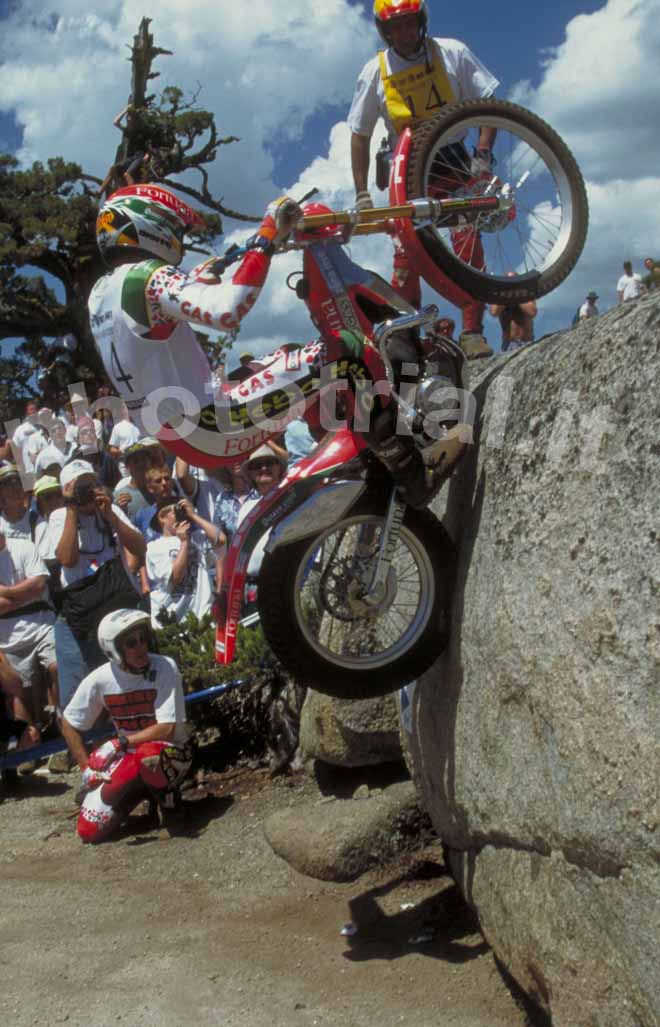

The time limit had recently been introduced in the sections because thanks to increasingly lighter motorbikes and riders who were increasingly virtuous with balance, the show was losing dynamism and the non-partisan public was becoming impatient. We started with 3 minutes and then moved on to 2. But the organizers were often sorry to give up the obstacles chosen for the world championship and the 2 minutes became too little.

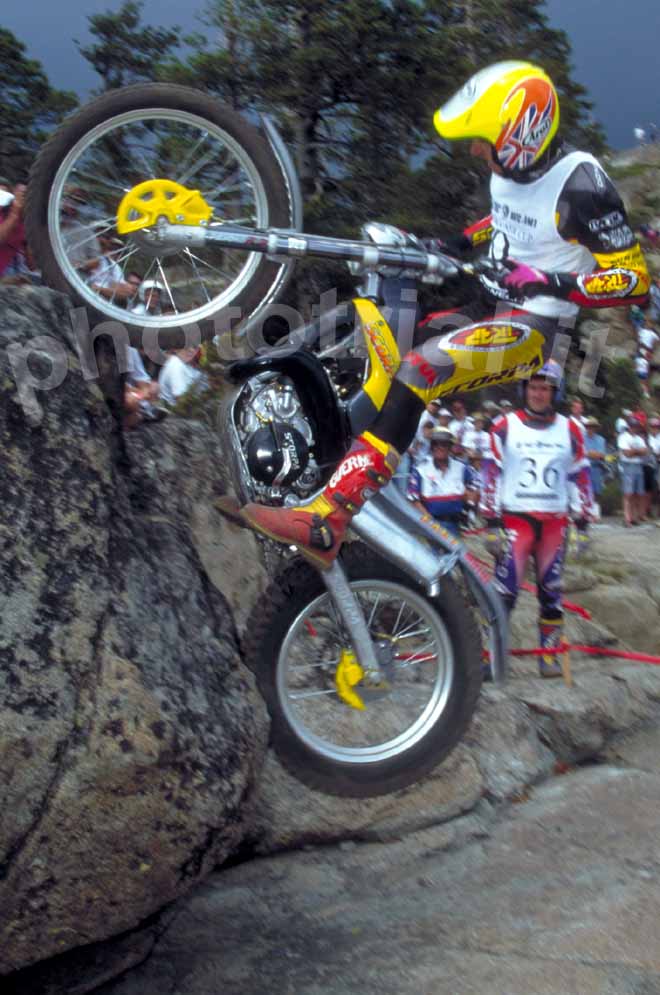

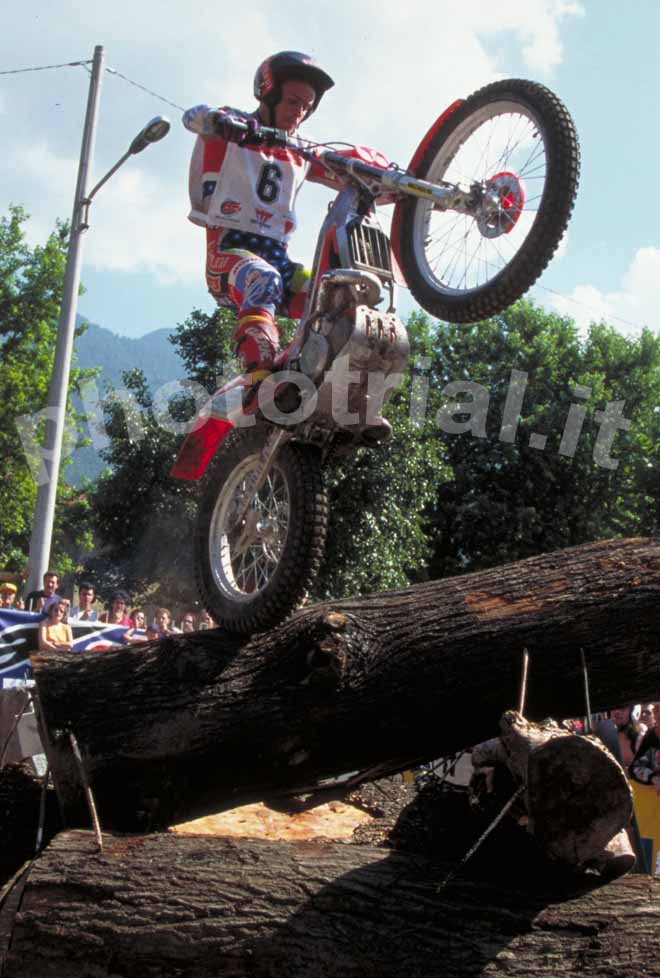

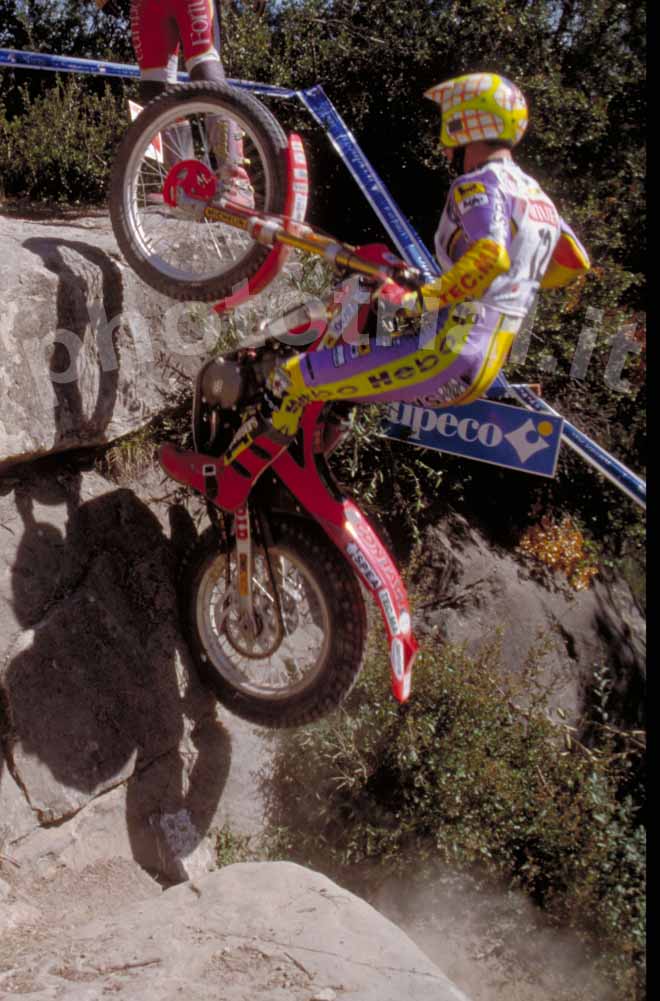

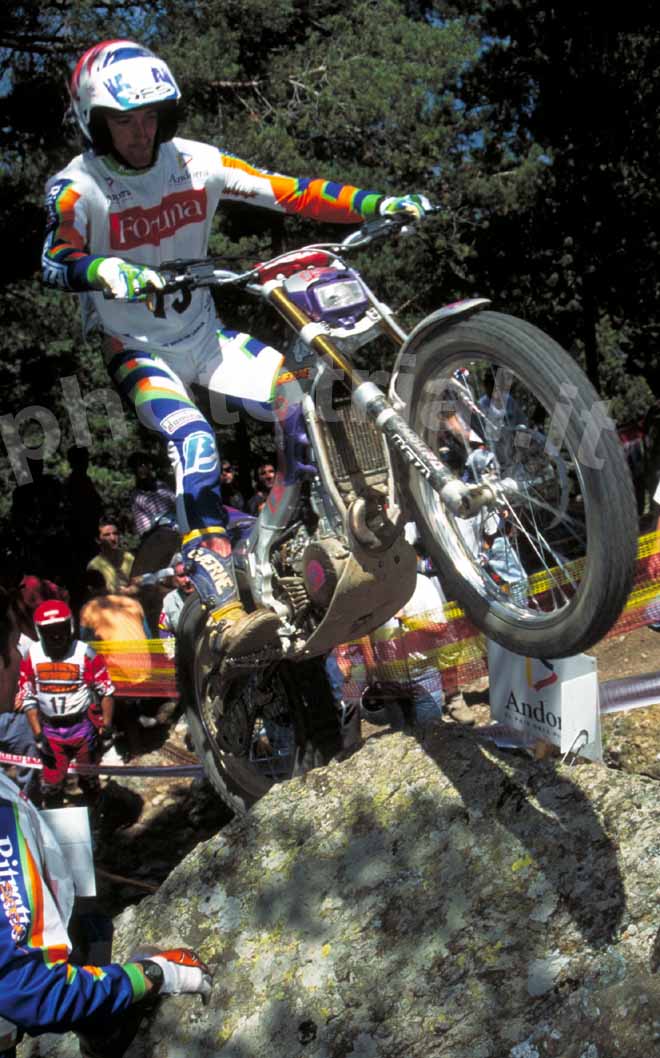

Precisely in 1997 (the images are from that year) with a view to simplifying the observers' work as much as possible, stepping back with the foot on the ground was also allowed. All allowed therefore within the time limit of 2 minutes.

It was a disaster: the Trial style was distorted and debased. Riders attempted the obstacle several times, struggling with enduro style: it was enough not to get off the bike. There was also a natural tightening of the sections, to maintain a fair selection, made more standardized by the greater possibility of exiting at "3". In short, no one liked it and it didn't last long.

The story will then take us to the much discussed non-stop several years later.

Changing the Regulations did not bring anything good, we can say today with hindsight.

But honestly Phototrial has always supported it even at the time and if you don't believe it you can read it in the Trialsprint collection published on Motosprint and today online by clicking here.

What is missing and has always been missing is a greater diffusion of this sport and not just the high-level one, that of tightrope walking, the one that makes you stand with your mouth open but which would never encourage you to try.

We must make known the extreme flexibility of this sport, which can be practiced by everyone at a low level, both sexes, young and old, which does not need special facilities, which also allows you to stay in physical shape by practicing it .

How many times have we written that taking advantage of the great visibility of arenas full of those who race to watch the indoor trials (now X-Trials), in the intervals between two phases, why do not project some videos of amateur riders having fun on Saturday or Sunday, who fall, get up and smile.

Only the base, the one always ignored, the one always sacrificed, can save the Trial.

The motorbikes must leave the manufacturers prepared for these people: so no more on-off clutches, inelastic engines, too hard suspensions. Jumping from one stone to another on the rear wheel is the privilege of a few, beautiful to watch, but discouraging for those who perhaps would have liked to start.

Better a few curves made by moving the weight than reasonably involving a greater age range of people. Because the Trial market has always been supported not by young people, who try and then quit, but by people who are no longer very young, whose passion is much more long-lasting.

Then there is nothing to prevent - as has always happened - top riders going to specialists to make their vehicle perform better or to adapt it to their personal riding style.

But it is absurd that the opposite happens, that is, the amateur has to have the newly purchased motorbike weakened in order to be able to use it!

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

E' colpa delle moto la crisi dei giorni nostri?

Recensendo il recente libro prodotto da Trials Magazine UK sulla crescita del campione Dougie Lampkin, sui sacrifici, sui lunghi tempi di alti e bassi prima di finalmente coronare il sogno, il primo titolo mondiale outdoor, nel 1997, il primo di sette consecutivi, ci è venuto spontaneo aprire una finestra su quell'anno, per confrontarci e capire dove abbiamo sbagliato, se abbiamo sbagliato perchè probabilmente nulla si sarebbe potuto fare, per evitare di arrivare alla profonda crisi dei giorni nostri.

Si parlava già di crisi all'epoca perchè dal boom degli anni 80 il Trial non è più cresciuto come numeri, ma tutto sommato erano rose e fiori in confronto a quanto sta accadendo oggi.

C'era chi sosteneva che le moto stavano diventando troppo sofisticate, adatte solo ad un utilizzo sportivo e quindi restringevano il bacino di utenza, con quelle selle inesistenti, con quei motori sempre più potenti e sospensioni sempre più reattive.

Ma il progresso non si poteva e non si può arrestare. La Federazione Internazionale stava iniziando ad agire sui Regolamenti, da troppi anni non toccati, pensando di creare nuove motivazioni.

Si era da poco introdotto il tempo limite in zona perchè grazie a moto sempre più leggere e piloti sempre più virtuosi dell'equilibrio, lo spettacolo perdeva in dinamismo e il pubblico non di parte si spazientiva. Si iniziò con 3 minuti per poi passare a 2. Ma spesso agli organizzatori dispiaceva rinunciare agli ostacoli scelti per il mondiale e i 2 minuti diventarono troppo pochi.

Proprio nel 1997 ( le immagini sono di quell'anno) nell'ottica anche di semplificare al massimo il lavoro dei giudici, venne permesso anche l'arretramento con il piede a terra. Tutto concesso dunque nel tempo limite di 2 minuti.

Fu un disastro: lo stile del Trial ne uscì snaturato, svilito. Piloti che tentavano più volte l'ostacolo, arrancando con stile enduristico: tanto bastava non scendere dalla moto. Ci fu anche un naturale inasprimento delle zone, per mantenere una giusta selezione, resa più massificata dalle maggiori possibilità di uscire a “3”. Insomma, non era piaciuto a nessuno ed era durato ben poco.

La storia poi ci porterà al tanto discusso non-stop diversi anni dopo.

Il cambiare i Regolamenti non ha portato nulla di buono, possiamo dire oggi col senno del poi.

Ma onestamente Phototrial lo ha sempre sostenuto anche all'epoca e se non lo credete lo potete leggere nella collezione di Trialsprint pubblicati su Motosprint e oggi in linea cliccando qui.

Quello che manca ed è sempre mancato è una più grande diffusione di questo sport e non solo di quello ad alto livello, di quello dei funamboli, quello che ti fa stare con la bocca aperta ma che non ti invoglierebbe mai a tentare.

Si deve fare conoscere l'estrema flessibilità di questo sport, che può essere praticato da tutti a basso livello, entrambi i sessi, giovani e vecchi, che non ha bisogno di impianti particolari, che permette anche di mantenersi in forma fisica praticandolo.

Quante volte abbiamo scritto che sfruttando la grande visibilità di arene colme di chi corre ad assistere ai Trial indoor (oggi X-Trial) non proiettare negli intervalli fra due fasi qualche video di piloti amatoriali che si divertono al sabato o alla domenica, che cadono, si rialzano e sorridono.

Solo la base, quella sempre ignorata , quella sempre sacrificata, può salvare il Trial.

Le moto devono uscire dalle Case preparate per queste persone: quindi basta frizioni on-off , motori poco elastici, sospensioni troppo dure. Saltare da una pietra all'altra sulla ruota posteriore è privilegio di pochi, bellissimo da guardare, ma scoraggiante per chi forse avrebbe voluto iniziare.

Meglio qualche curva fatta spostando il peso che ragionevolmente più coivolgere un range di età maggiore di persone. Perchè il mercato del Trial lo sostengono da sempre non i giovani, che provano e poi smettono, ma gente non più giovanissima, la cui passione è molto più duratura.

Poi nulla vieta – come del resto è sempre successo - che i piloti di grido vadano dagli specialisti per rendere il proprio mezzo pù performante o per adattarlo alla loro personale guida.

Ma è assurdo che succeda il contrario, ossia l'amatore che si deve far depotenziare la moto appena acquistata per riuscire a utilizzarla!

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------